The relationship between professional sports franchises and the cities they represent seems to be teetering on the brink of collapse, particularly in the NBA. However, transiency in professional leagues is nothing new; indeed the two cities in imminent danger of the losing their NBA franchises, New Orleans and Sacramento, acquired their respective teams from other cities years ago. Furthermore, this would be the second NBA squad to leave the Crescent City since the merger [see photo]. Teams have been switching cities ever since they started representing them. Exactly half of the franchises in the NBA started in a place that they don’t currently occupy.

This transiency seems odd considering how much of the corporate identity and economy of each franchise is tied to its geographic location. Teams have city and state names stitched into their uniforms, rely on local government funding for their facilities, use local and regional imagery in their marketing materials and logos, and, most importantly, depend on season ticket revenue from residents living in the same region. The relationship is not purely parasitic, however. The economic, social, and political impact of professional sports organizations on their cities has been well documented [I’m guessing since I haven’t actually looked]. If this symbiotic relationship works, why are so many teams swapping locales?

Naturally, the superficial response is “market forces.” Certainly, one can imagine that the opportunity for profit is higher in Brooklyn than in New Jersey, in Anaheim than in Sacramento. It is not quite that simple, however. What does Oklahoma City have to offer that could not be had in Seattle, and what does Salt Lake City hold over New Orleans? The truth lies in the perks of novelty. It is much easier to market a franchise in a mid-sized city if it has a new arena, an optimistic outlook [no one is thinking about the Thunder’s imminent departure from Oklahoma yet], and a motivated local government than one with used facilities and fans tired of mediocrity and disloyalty. Revenues are buoyed by a change in venue, but only temporarily.

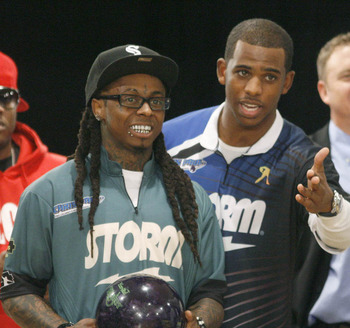

An argument could again be made dynamic companies are more competitive. Rosters change weekly. This is also nothing new, regardless of how people may feel about “The Decision.” LeBron’s flight to South Beach hardly outshines Shaq, Gretzky, or Wilt’s respective trips to LaLa Land. Something does seem different now, however. Organizational transiency makes teams too reliant on the whims of the individual players to maintain their marketability. Take the situation the New Orleans Hornets find themselves in, for example. Nearly all of their current value is tied to the marketability and competitiveness of their best player, Chris Paul. However, both the Hornets and Paul are rumored to be on their way out of the Dirty South. If Chris commits to the city, ticket and merchandising sales will continue and we may have a fighting chance of keeping the team. The paradox lies in that once he leaves, the only people that would care about a talentless Hornets squad are those that have emotionally invested themselves in the franchise; i.e. the people of New Orleans. The team will suddenly be dependent on the people of the city it is considering abandoning just to stay afloat. Or they could bail. The Hornets and NBA can either invest in the city for the long term, permanently ingraining itself into the culture and psyche of its people or flee for the fast cash and flash of a new market. Those guys are going to leave town faster than a GM executive driving a Camry through Flint.

The negative economic impact on the city will take time to overcome but the true casualty of the NBA’s imminent flight from New Orleans is the long term value of the franchise itself. Ask any first year MBA candidate what the most valuable asset an established company has and they will undoubtedly respond simply “brand.” Teams that have successfully tied themselves to a place are by far the most stable. Teams whose brand is tied to the team’s personnel suffer when popular players are traded, leave as free agents, or retire. The NFL is packed with teams that are incomprehensible in any other location [Packers, Steelers, Saints, 49ers, etc, etc] and it has little do with market size. These franchises are economic powerhouses because of their dependency on place, not in spite of it. Now imagine that the New Orleans Jazz had never fled for Utah. The team would have decades of memories, personalities, and loyalties to draw from and fall back on in the event that a franchise cornerstone chose to leave. Just as the Packers survived the departure of Favre, New Orleans would soldier on after CP3.

The argument that the city has not shown the Hornets the necessary support to sustain the franchise is superficial and short sighted. The team has been here only since 2002 and has been bad for most of that stretch. It takes time to develop a relationship with a community. It takes even more time to make oneself indispensable to that community. Why would local fans step up and invest in a team financially if they barely had the time to establish an emotional attachment to them before rumors began circulating that they were going to leave?

Cities will also suffer from continued transiency for reasons beyond the fiscal. Just as freeways, cookie cutter subdivisions, and shopping malls have propagated the American “non-place” phenomenon, franchise mobility hurts urban identity. Like it or not, sports are important to people and people make place. Competition encourages local pride and engagement. Engagement encourages investment. Investment benefits all the residents of a city; fans, athletes, and owners alike.

In the era of free-agency, long term organizational solvency is only possible through fixed occupancy. Cities need teams. Teams need cities. It is high time that the commitment started working both ways. It’s good business.

No comments:

Post a Comment